Pregnancy and Chemotherapy

For a long time, doctors did not give chemotherapy to pregnant women, and women of child-bearing age who received chemotherapy were advised to take precautions against pregnancy. If a pregnant woman got cancer, the pregnancy was either terminated or early labor was induced. While this is still the accepted best practice for oncologists in most cases, there is some science indicating chemotherapy may not be as detrimental to fetal development as feared.

A small study presented at the European Multidisciplinary Cancer Congress found just that. The scientists examined women who received chemotherapy while pregnant. They looked at the effects of the drug on the baby’s heart and nervous system and general health. The researchers had complete data on fewer than a hundred children, but none of them were born with congenital heart defects. Many of the babies were delivered prematurely, although it is not clear that the chemotherapy was the only or main factor in causing early delivery.

The babies who were born at full term had normal health and cognitive development at age 18 months. While larger studies are needed, this is an indication that “the fear of chemotherapy should no longer be an indication to terminate a pregnancy” according to what one research told the press. The president of the European Cancer Organization was quoted as saying a “paradigm shift” may be in the works on this issue.

One reason oncologists have been reluctant to use chemotherapy on these patients is the lack of clinical trial data: pregnant women or women likely to become pregnant are excluded from these trials. Some doctors feel immunotherapy and other targeted therapies are safe enough to risk in use during pregnancy.

Chemotherapy agents crossing the placenta?

How big of a problem is this? About 0.1% of pregnant woman are diagnosed with cancer.

The old-time chemotherapy agent methotrexate, still widely used, is also used in medical abortions. It induces miscarriages. Chemotherapy drugs can cross the placenta, and the cytotoxic effects of cancer drugs would seem logically to be detrimental to fetuses, or at least embryos. Teratogenicity is listed as a potential side effect for some chemotherapy agents and there are case studies of babies being born with defects after chemotherapy. (However, a study in baboons showed the placenta blocked most of the chemotherapy from the fetus, so exposure was much lower than in the mother’s tissue. Further work is needed in this area, but people are excited about the possibilities.)

A review of chemotherapy administration to pregnant women found that after the first trimester of pregnancy there is not a substantial increased risk of malformations but there is increased risk of stillbirth and intrauterine growth restriction.

When pregnant women have been given methotrexate during the first trimester, the baby sometimes ends up with malformations similar to the aminopterin syndrome.

There is scant evidence on the safety of chemotherapy for women who are breast feeding and whether the chemotherapy drug passes through the milk to the baby. The immunosuppressive drug azathioprine has been shown to not show up in breast milk in significant concentrations.

There is scant evidence on the safety of chemotherapy for women who are breast feeding and whether the chemotherapy drug passes through the milk to the baby. The immunosuppressive drug azathioprine has been shown to not show up in breast milk in significant concentrations.

This has not been shown for other chemotherapy drugs, and in general, doctors tell women who have recently given birth to not breast feed. The benefits of breast feeding for the baby do not outweigh the risk of exposure.

Further, if a woman has had cancer when pregnant, the placenta is examined for malignant cells when the baby is born.

Related: Woman nurses who handle chemotherapy drugs more likely to have miscarriages.

Menopause and Chemotherapy

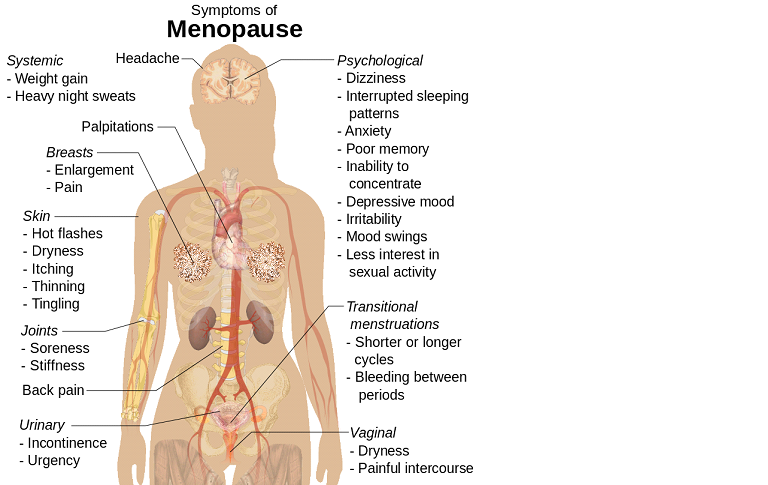

Menopause is a the time in a woman’s life when she stops having periods – the permanent cessation of menstruation at the end of reproductive life due to loss of activity of ovarian follicles. It can be confirmed by amenorrhoea for 12 consecutive months, without any other pathology.

Chemotherapy treatment in women often drives the development of menopausal symptoms. Many studies have been conducted on the relationship between chemotherapy and menopausal symptoms.

Scientists have found chemotherapy treatment is not associated with present vasomotor symptoms (bot flashes or flushes, night sweats etc.) or psychological symptoms (anxiety, depression etc.). The main symptoms noted in adjuvant chemotherapy were severe pain during intercourse.

During treatment women may experience irregular menstrual cycles or complete cessation of periods. These symptoms may be temporary or permanent depending upon the age of the patients. In young patients, these problems can return back to normal after a period of time.

Ovarian toxicity can be an important concern in young patients who receive chemotherapy with a curative intent. Treatment can cause a decline in fertility potential as well as menopause-associated comorbidities. Menopausal symptoms induced by chemotherapy may last for years after treatment is completed.

Dosing, amount and type of chemotherapy are very important. In patients under 40, the chances of menopause inducement from therapy is low, but in patients over 40 it becomes more likely.

There is no way to definitively predict when and how chemotherapy will influence menopausal symptoms and to what extent. Younger women can usually resume their normal life within few months to years after treatment. Major concerns are the cessation of periods and post-coital severe pain.

References:

http://journals.lww.com/menopausejournal/Abstract/2016/09000/How_does_adjuvant_chemotherapy_affect_menopausal.10.aspx

D.C. Dutta/textbook of gynaecology/6th edition//cp. 6/pg. 56

http://journals.lww.com/menopausejournal/Abstract/2016/09000/How_does_adjuvant_chemotherapy_affect_menopausal.10.aspx

Obs and Gynae an evidence-based textbook for Mrcog/Edition 2nd/ Ch. 56/Pg. 642

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0140842

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/beauty/skin/menopause-care/chemotherapy-induced-menopause/

Today’s arsenal of chemotherapy agents includes many different classes of medicines. Researchers continue to find and test new drugs.

Today’s arsenal of chemotherapy agents includes many different classes of medicines. Researchers continue to find and test new drugs.